Isolated. Confined. Extreme.

What it's like to live in Antarctica and what we can learn from people who do.

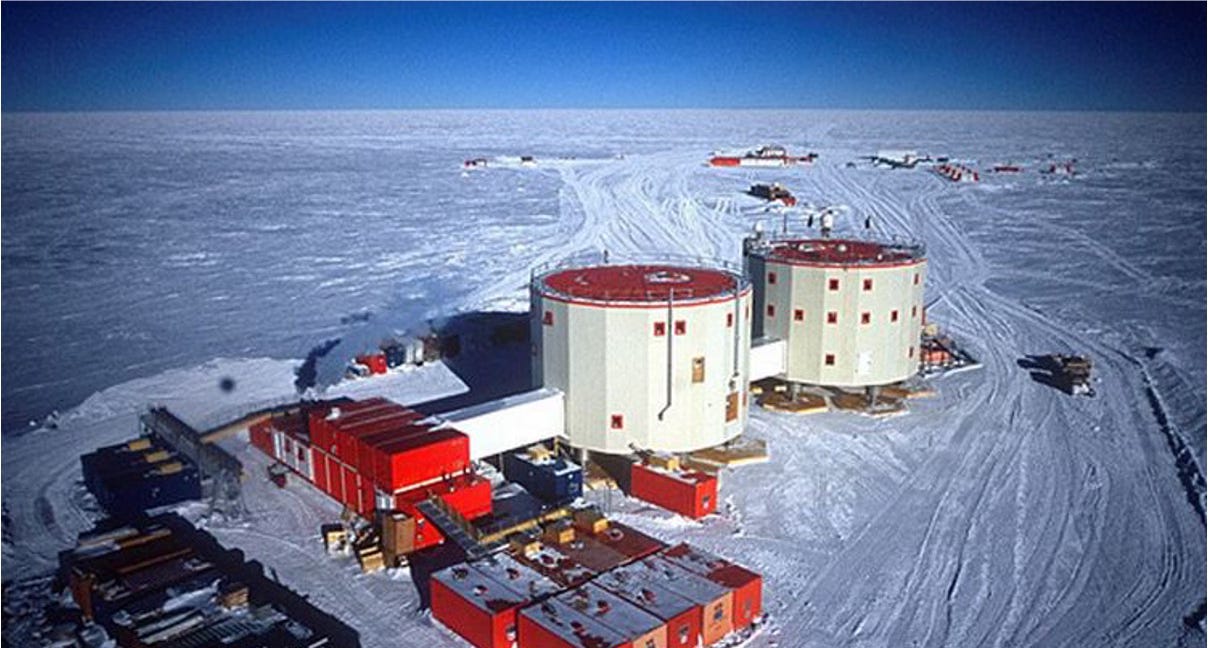

Introducing Concordia, an “ICE” environment

Whilst at the European Space Agency, I didn’t just work with Astronauts. I also worked with a group of terrestrial explorers who volunteered to live and work in a remote Antarctic research station named Concordia for over a year.

We did this because although Concordia crews weren’t travelling to space they had more in common with Astronauts than you might think. For their year-long deployment:

- Their colleagues were all they had for real company,

- They lived in claustrophobic, industrial habitats,

- The environment outside could kill them,

- They were taking extreme risks,

- They couldn’t leave,

These characteristics are so specific (and interesting to people like me) that they have a special name. We call places like this ICE environments, which stand for Isolated, Confined and Extreme. Space stations, submarines and Antarctic outposts are all ICE environments.

How ‘ICE’ is it?

The Concordia research station sits at 3200 meters above sea level. The weather there is brutal - it gets as cold as -80°C in winter, and the average temperature throughout the year is a freezing -50°C.

Since it's located at Earth's southernmost point, the station experiences some interesting daylight patterns. For four months, you won't see the sun at all in winter, while in summer, it never sets.

Living there is really tough. The air is super thin due to the high altitude and holds less oxygen, so you've got to bundle up in tons of layers whenever you step outside, and you can't stay out for long. During winter, you're completely cut off - no planes or vehicles can reach you, so you have to handle any problems yourself.

It's so dry that the crew continually have to deal with cracked lips and irritated eyes.

No cute penguins either - the environment is so harsh that no animals can survive in this region, nor most bacteria. Your closest neighbours are at the Russian Vostok base, about 600 km away - making you more isolated than astronauts on the International Space Station!

The landscape is pretty eerie - a vast, dark emptiness with hardly any colours, smells, or sounds. This extreme isolation and lack of sensory input really messes with your body clock, making it hard to get a proper night’s sleep.

We treated Concordia as an analogue for spaceflight. Somewhere that’s not exactly the same as going to the space station, but from a psychological perspective, it’s close enough. The idea was that we could draw parallels between the psychological effects of staying in Concordia and, say, future long-duration space missions, like Lunar colonisation or a Mars mission. This helps us prepare astronauts for the psychological impact of space exploration and to modify mission plans to mitigate any issues.

How did group dynamics evolve during 14 months of isolation?

Every year, a winter-over crew of roughly 14 have to prepare for, deploy to, and be supported through 14 months of life in the middle of Antarctica (and up to 80 people during the ‘summer’ months). The team is a real cross section of society. From research scientists, to chefs, to plumbers, electricians and medical doctors, all living and working together, isolated from the outside world, in a very hostile environment, for a whole year.

This led to some pretty interesting group dynamics.

Their journey started with preparation. Although we spent some time training them in optimal human performance before they deployed, the crew had a lot of other tasks to complete, and they were often visiting different research institutes in different countries at different times for technical training, medical testing, and preparation before they deployed.

When the winter-over crew came to our training at the astronaut centre, this was often the first time they had all met. When they all arrived at Concordia with the summer crew, again they had to reform into a much bigger team, building their group dynamics on the fly whilst they got to work.

Later in their mission they experienced further disruption when the initial summer crew of 80 dwindled to 14 for what’s called the ‘overwinter’ period.

I worked with several Concordia teams to prepare them for their mission, and there were three key trends I observed, which I think are interesting for us today:

1. An informal leader often emerged

During the debrief held after each mission, we often found that the person selected to lead the team didn’t necessarily become the go-to person for the rest of the crew. Nor was it the person with the most technical, or scientific background.

Instead, the person with the most experience of Antarctica often became the de-facto leader. On more than one winter-over, this was also the person who brought people together and cared for the crew.

That leader was, on more than one occasion, the Chef. Someone who’d lived through multiple missions and knew what to do and what to expect from the winter and the crew. He also had the role of bringing people together to eat, which enabled social interactions and improved team dynamics. Quite often, during the long winter, the meal was the highlight of the day.

2. Better contact with friends and family was actually a problem for group dynamics

We also found that isolation became a concern when crew members spent too much time alone in their rooms instead of engaging with the team. An interesting development occurred when they introduced faster Wi-Fi on the base. Previously, team members made considerable effort to bond and get along with each other as they were all they had. Once they could easily connect with friends and the outside world via the internet, it actually created problems within the team stationed at the base, as they spent less time and effort socialising together.

3. The dramatic changes in group size and responsibilities caused major fluctuations in group dynamics

The Antarctic summer-winter transition presents another unique challenge. During summer, around 80 people are at Concordia base. When winter approaches, most leave, leaving just 14 core crew members. Such a dramatic re-org forces the winter team to reform their dynamics and go through the forming-norming-storming process all over again (see the model below). When the weather improves, everyone returns, causing a second dramatic change in group dynamics during the mission. Every time, people reported significant issues as everyone readjusted to their position in the social order.

What does this mean for you?

Maybe you’re a manager with a team you’d like to energise. Maybe you’re a boss trying to figure out why a team doesn’t seem to be ‘clicking’. Maybe you’re a team member who wants to change how you feel about work and your colleagues. What can you do with these findings?

1. Leadership isn’t just a title.

I can think of several examples outside Concordia, of teams rejecting the leadership imposed by a hierarchy in favour of the person they sense is the strongest leader. This can be managed well, or badly.

My advice to organisations is to choose wisely and don’t rush in. For example, when Astronauts are assigned to missions there is some politics involved, but there’s also a considered review process using tools like team matrices to ensure everyone’s skills compliment each other. And the ISS leader is always someone experienced, who’s flown before.

But what if you’re that leader with little experience, thrust into a position of authority? This happens a lot. People on fast track schemes, and perhaps Army Officers in their first appointments are good examples1. Things which can help you succeed when you don’t have experience on your side include:

- Acting with self awareness and treating the role as a growth opportunity. Don’t act like you know it all ‘because a leader should’, instead listen, learn and synthesise - prioritise building trust.

- Establishing trusted advisors. In the military this is actually ‘done for you’, since a fresh Lieutenant will be partnered with a grizzly Sergeant whose job it is to act as a mentor. Find your own Sergeants and build partnerships with them.

- Concentrate on your values, not your knowledge. People respond to solid values like courage and integrity wherever they come from. Build trust with your team by sticking to these virtues. They’ll appreciate you despite your inexperience.

2. Make time for your team to socialise

Maximum productivity isn’t the result of a slavish work schedule. We are social animals. Teams who only interact to produce the work they are paid to deliver miss out on opportunities to develop group dynamics which enhance their overall productivity and net out to increased productivity in the long run.

Sharing experiences other than work expose colleagues to different challenges, even utterly benign ones, which bring them closer as a group and enhance characteristics like trust, loyalty and mutual respect, which are incredibly important for a group’s productivity.

Try:

Increasing (or introducing) away days, where teams help each other to complete challenges they wouldn’t face at work (think: escape rooms). or,

Introducing team sports during work hours. As this meta analysis by Loughborough University suggests: “team sport holds benefits not only for individual health but also for group cohesion and performance and organisational benefits such as increased work performance.”.2

Another activity I’ve seen championed by leaders is taking the team out to ‘cook their own food’, after a leadership workshop or similar. Learning something new together is always a good opportunity to share a bit of vulnerability, safely.

The important thing is to get outside the context of the workplace so that people can socialise together rather than work together. We have different personas depending on context and the best teams are ones which have strong bonds inside and outside of the work environment.

3. Prioritise group stability and avoid frequent re-orgs

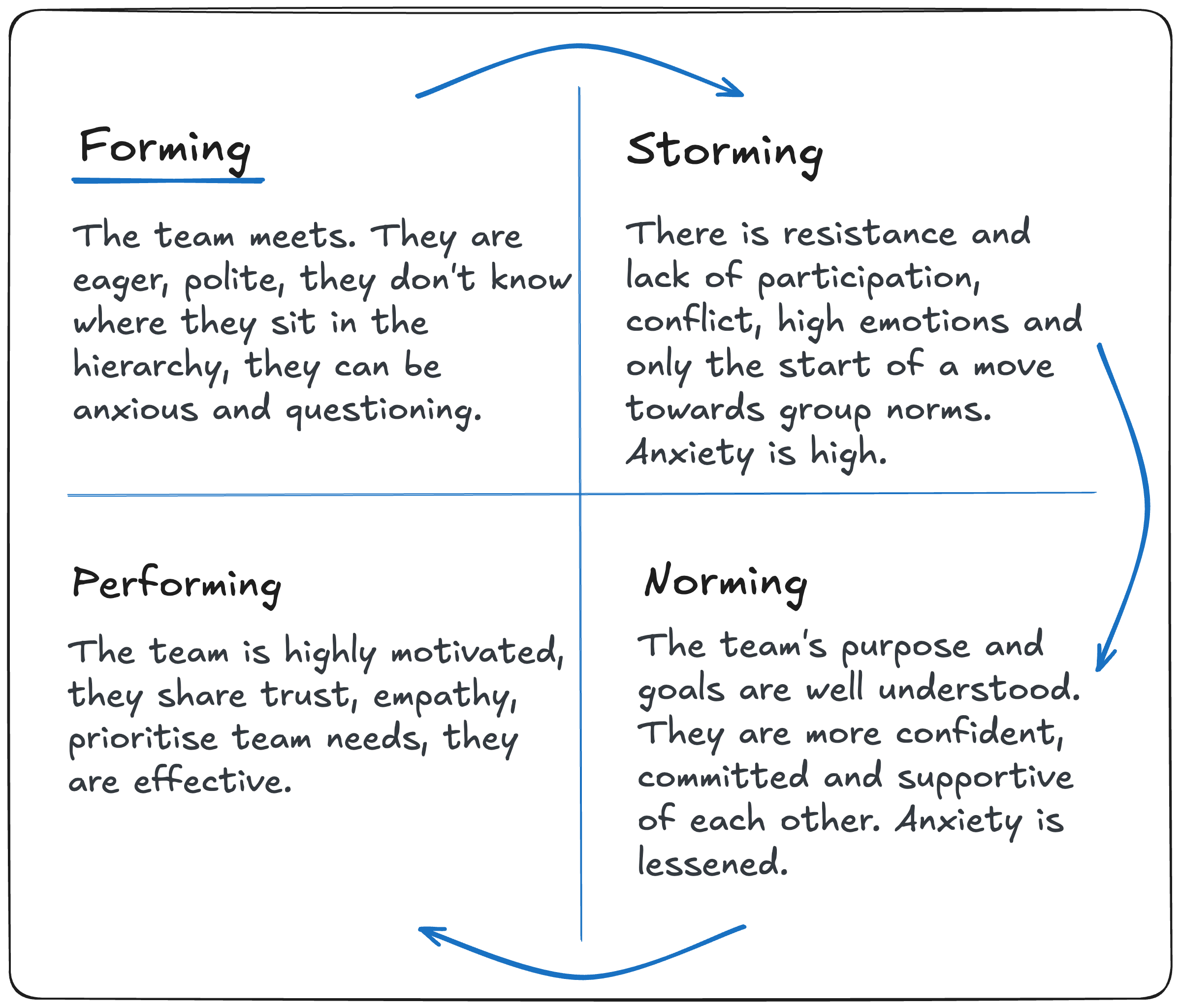

You may be familiar with the terms: Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing. This is because they are phases of Bruce Tuckman’s well known model for Group Development.

It’s a handy model for explaining the social and organisational steps a group of people go through when they are building a team:

I could write an article on these phases (maybe I should?) but the key takeaway today is that re-organisation is expensive. When groups first come together, because they are brand new, or they are being re-organised, you are adjusting the social structure. This is deeply harmful for productivity because the first three phases of the process (Forming, Storming and, to a lesser degree, Norming) are all sub-optimal for productivity.

Major re-orgs should be carefully considered before they are implemented and only when there really is a problem that needs solving.3

What do you think?

I hope you got something out of today’s article. If I’ve told you something new or inspired you to take some action, I’d love to hear about it. Likewise, if the issues I’ve raised are real for you, feel free to DM me, I’d love to hear your story!

Usually, Army Officers are trained straight out of university and then given their first ‘command appointment’ as a platoon commander or similar, right after they finish. They can be the youngest person in the platoon and also the person ‘in charge’. ↩

Although it’s true that it might take some thought to make team sports inclusive. ↩

If you are thinking of running a re-org, Will Larsen (an Engineering Manager and author) has a good set of thoughts as a starter for ten. ↩